Overview: Regulation of biopesticides

In this seventh article of a series on BioPesticides, I present a brief overview of Biopesticide Regulation in Crop Protection, with a primary focus on the US and EU frameworks. If this article provides value, please consider liking and sharing. Your feedback is invaluable, and helps new readers discover my work!

Biopesticides (microbial pesticides, bio-derived chemicals and plant-incorporated protectants) introduce unique and complex modes of action and may be used in plant production on an equal footing with chemical pesticides

Even though biopesticides have been commercially used for over 60 years, they have generally been evaluated and registered following the model for the registration of conventional pesticides, and laws and policies regulating their use vary from country to country.

Submission procedures have often been lengthy, and the high cost of registration has limited the commercialization of new and safer biopesticidal products, particularly in the EU.

However, many of the data requirements (such as chemical identity) and evaluation criteria may not be relevant for most biopesticides, and risk levels for environment or human health safety are (generally) considered to be lower than for conventional pesticides.

In the following, an overview of biopesticide evaluation and registration is presented, with a primary focus on the regulation of biopesticides in the US and EU.

US

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for regulating pesticides, ensuring they do not pose adverse effects to humans or the environment.

The Biopesticides and Pollution Prevention Division (BPPD) falls under the EPA and is responsible for all regulatory activities associated with biopesticides.

Biopesticides are recognized as a regulatory category and are regulated following a different set of data requirements than for conventional chemicals.

Biopesticides as a category are typically considered by EPA to be “reduced risk pesticides” – of lower risk than conventional pesticides. However, biopesticides are not necessarily harmless, despite being of natural origin – the formation of plant-produced toxins induced by biopesticides is a case in point.

Genetically modified microbial pesticides (plant-incorporated protectants) are evaluated on a case-by-case basis depending on the microorganism, proposed use pattern and nature of the genetic modification.

EPA registration is not required for semiochemicals (e.g. pheromones) used in fixed-location lures to attract and monitor pests, with minimal impact on either the environment or human health.

Not all natural products are able to be registered as biopesticides. For example, pyrethrins, spinosad and abamectin are registered by the EPA as conventional (chemical) pesticides due to their neurotoxic mode of action.

In contrast, Azadirachtin (a botanical insecticide extracted from natural neem oil) acts as an insect growth regulator, anti-feedant, repellent, sterilant, and oviposition inhibitor and is registered as a biopesticide

The EPA generally requires fewer data for biopesticides than for conventional pesticides (with e.g. most pheromones being exempted for testing) and biopesticides may be subject to exemptions from residual tolerance levels. This last point, however, is contentious, as it potentially hinders global trade to regions with maximum residue levels in food (such as the EU), reducing the potential economic viability of new biopesticides and thus their introduction into global crop protection strategies.

The biopesticide registration process may begin with an electronic pre-submission consultation request, for which the EPA will provide specific guidance for application.

The registration process continues with the formal submission to the BPPD of a pesticide registration application, which leads to an initial content screen, followed by a preliminary technical screen. If no issues are found, the formal science (including chemical-physical, toxicological and ecotoxicological) review process is initiated.

Registration of biopesticides takes 12 to 18 months, compared to approximately 36 months for conventional pesticides, and registration fees are lower.

EU

Fewer biopesticides are registered in the EU than for example in the United States, South America, India or China, due to lengthy and complex registration processes in the EU, which follow a risk-based approach to the registration of pesticides – including biopesticides.

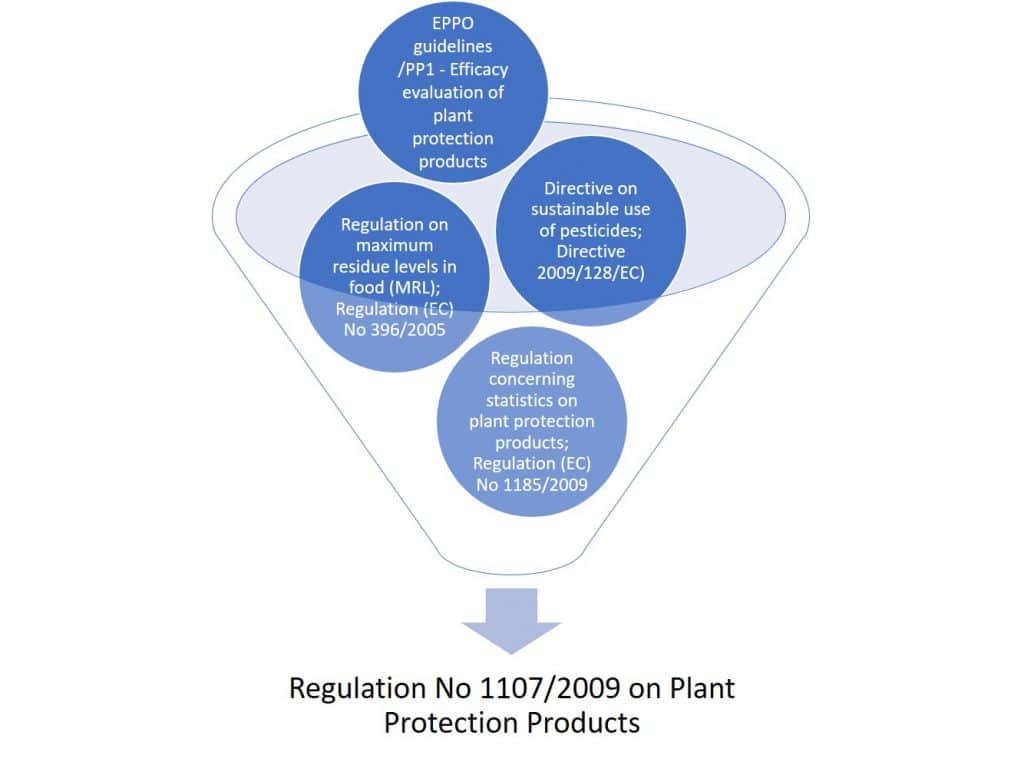

Biopesticides are regulated as plant protection products under EU plant protection Regulation 1107/2009, which – unlike the EPA – does not recognise “biopesticides” as a regulatory category.

Regulation is carried out in conjunction with other EU Regulations and Directives (e.g. the Regulation on Maximum Residue levels (MRLs) in food; Regulation 396/2005) and the Directive on sustainable use of pesticides; Directive 2009/128/EC).

Figure 1: Regulation of Plant Protection Products in the EU.

Directive 2009/128/EC aims to advance the sustainable use of pesticides, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and the use of non-chemical alternatives to pesticides – including the development and use of biological pesticides.

Following approval, a monitoring program ensures pesticide residues (Maximum Residue Levels; MRLs) in food are below the limits set by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

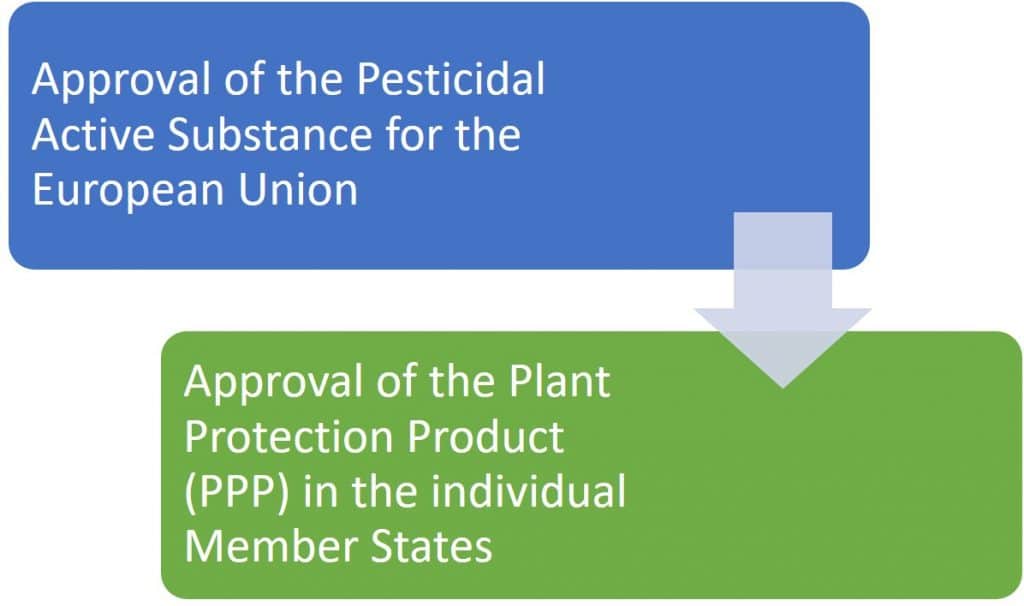

Before pesticides can be introduced to the European market, the pesticidal active ingredient (active substance) must be approved for the European Union, after which approval of the Plant Protection Product (PPP) can be sought in individual Member States.

Figure 2: Two-tiered approach for the approval and authorisation of pesticides in the EU

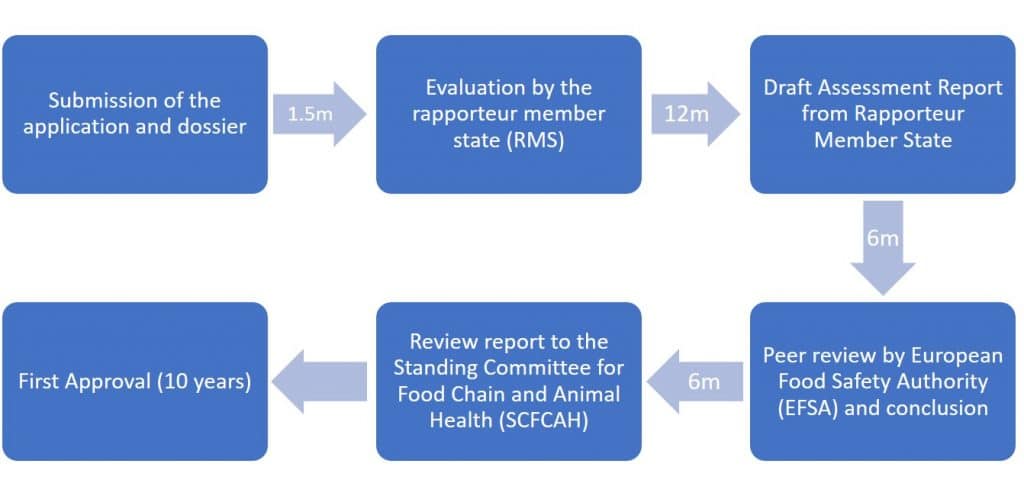

For the approval of a pesticidal active ingredient (active substance), the applicant submits a dossier containing supporting scientific data (including efficacy, chemical-physical, toxicological and ecotoxicological, analytical methods to determine purity and potential residues, as well as environmental fate, residues and operator exposure studies) to a Member State (Rapporteur Member State).

The Rapporteur Member State evaluates the application and, if the dossier is considered admissible, the Rapporteur Member State starts evaluating the active substance.

The Rapporteur Member State produces a Draft Assessment Report, which is submitted to the European Commission and EFSA, who is responsible for the peer reviewing of the risk assessments on active substances.

Figure 3: Procedure for Active Substance approval; EU (minimum duration in months, m)

Finally, the European Commission presents a review report to the Standing Committee for Food Chain and Animal Health (SCFCAH), who votes on approval or non-approval of the active substance.

Depending on the complexity and completeness of the dossier, it takes 2.5 to 3.5 years to approve a new active substance.

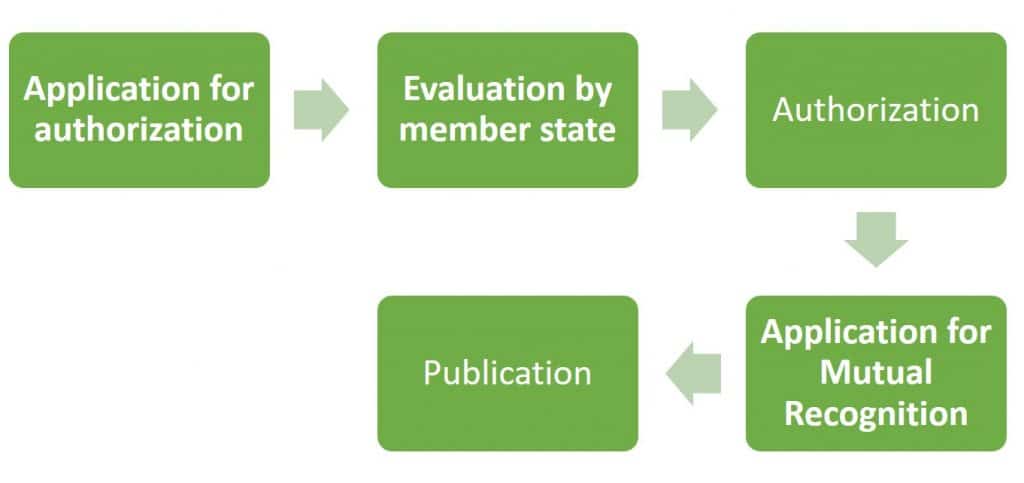

The subsequent authorization of a plant protection product (PPP) is carried out by the Member States, with the applicant specifying the Member State carrying out the evaluation. Multiple dossiers (for the product, for each active ingredient, a draft product label etc.) are submitted.

Figure 4: Procedure for Plant Protection Product approval; EU.

The authorization process for a PPP may not exceed one year. Following authorization, a company may apply for mutual recognition within one of the three geographic zones (North, Central, South) for products with the same use(s) under similar agricultural conditions.

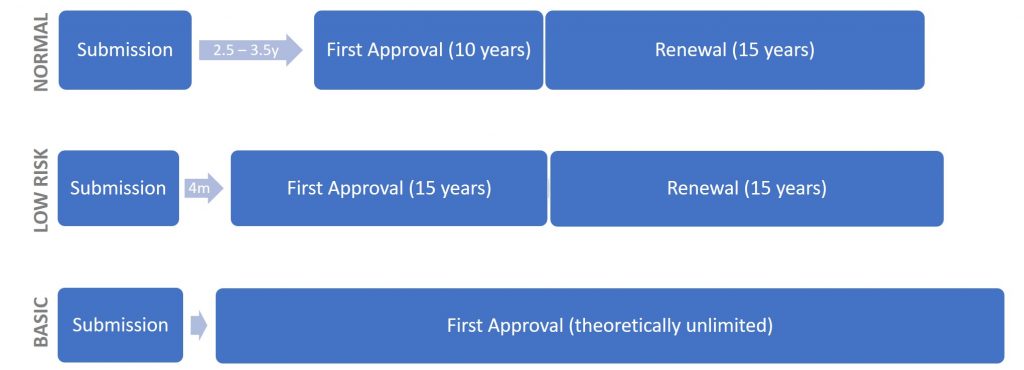

Although “biopesticides” do not exist as a regulatory category, the pesticide categories “basic substances” and “low risk substances” were introduced in August 2017, as defined in Regulation 2017/1432, amending Regulation 1107/2009.

A risk-based approval approach is used in the EU, as biological substances are not necessarily harmless, despite being of natural origin.

While a reduced dossier may be submitted for low-risk substances, this does not preclude the demonstration of sufficient efficacy. Biopesticides should generally qualify as low-risk active substances, facilitating the faster introduction of biopesticide candidates which fall under these categories.

Currently, 18 basic substances and 10 low risk substances are approved under Regulation 1107/2009.

Table 1: Low Risk Active Substances and Basic Substances approved under Reg. (EC) No 1107/2009.

Basic substances are substances not primarily intended as crop protection products, but which could provide crop protection capabilities, and their approval is based on existing evaluations carried out in accordance with other EU legislations. Authorisation is issued for the entire EU for an indefinite period.

Low risk substances must fulfil criteria listed in Annex II of Regulation 1107/2009. In contrast to conventional pesticide active ingredients, approval of low risk substances may be granted in part based on literature data and scientific reasoned opinions.

Microbial pesticides, baculoviruses and semiochemicals (e.g. pheromones) are assessed for compliance with low-risk criteria.

Assessment (evaluation) of low risk active ingredients (regardless whether of biological or synthetic origin) takes 120 days, compared to 12 months for conventional active ingredients, and low risk active ingredients are approved for 15 years, instead of the normal 10 years. In addition, authorisation fees are lower – factors promoting the introduction of low-risk products (including biopesticides) by smaller companies.

Figure 5: Assessment and approval timelines (y/m; years / months) for active substance approval; EU special cases.

For biopesticide development projects, due diligence should be applied to study design to ensure that the scientific requirements for potential inclusion in a registration dossier are met.

Biopesticide evaluation and data requirements

Many biopesticidal active substances (both bioderived chemicals and microbes) are well-documented, and significant parts of a dossier could comprise information from published literature, while waivers for data on residues, environmental fate and ecotoxicology may be considered based on scientific evidence, keeping in mind that natural substances are not necessarily harmless.

For groups of microorganisms having common properties, exchangeability of data could reduce registration time and facilitate the rapid introduction of new technologies for biopesticide strategies.

For many biopesticides, formulation components are inert or of no toxicological concern, and risk assessment may be based on the active substance alone, and on the basis of scientific evidence.

Harmonization of Registration Guidelines

As a result, registration guidance for biopesticides is being amended at international, national and regional levels by several organizations, including FAO, the International Organization for Biological Control (IOBC), European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO), the Organization for Economic and Co-operative Development (OECD), the European Union and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Many (but not all) countries and organizations differentiate between biopesticide and conventional pesticide registration, and advocate a harmonized approach to biopesticide registration, either through provisions for biopesticides in existing pesticide legislation, or through separate legislation for biopesticides.

Harmonization permits the exchangeability of data across countries and regulatory agencies, and regulations promoting the registration of low-risk compounds will facilitate the commercialization and use of biopesticides in crop protection strategies.

Further optimization

At global and regional levels, harmonization of accepted residue levels (tolerance levels) could promote global trade, increasing the economic viability and introduction of new biopesticide strategies.

While Regulation 2017/1432 (introducing the pesticide categories “basic substances” and “low risk substances”) facilitates the development and introduction of sustainable, non-chemical alternatives to pesticides in accordance with directive 2009/128/EC, further optimization of the regulatory process could advance the use of biopesticides in the EU.

Within the EU, harmonisation of the implementation of Regulation 1107/2009 between Member States could accelerate regional acceptance of biopesticidal strategies.

While “fast-track” approval of low risk active ingredients is beneficial, the registration process could be further optimized through a staged approval process: an initial rapid assessment of low risk criteria during the development phase to be followed by full evaluation.

Finally, certain plant biostimulants – currently regulated as fertilizers – could be considered for inclusion in a “special cases” category of the plant protection regulatory framework, exploiting their benefits to crop vitality as a factor in pest and pathogen resistance.

***

Thanks for reading – please feel free to read and share my other articles in this series!

PESTICIDES & BIOPESTICIDES: FORMULATION & MODE OF ACTION – the first book in the LABCOAT GUIDE TO CROP PROTECTION series is now published and available in eBook and Print formats!

Aimed at students, professionals, and others wishing to understand basic biological aspects of Crop Protection, this book is an easily accessible introduction to essential principles of Pesticide and Biopesticide Mode Of Action and Formulation.